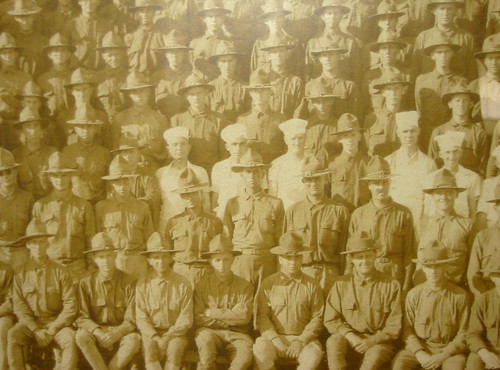

Photograph of a Photograph

A YEAR

CCVIII

Undetach’d, the morning invades piece-

meal, Stimmenimitatorlich, through the white

noise of night. It obtrudes

its exemplary barbarity in ditty,

snatch hummables, it samples its

wrought-up fervency in endless

insolvent répétez, répétez encores of

strut. It yanks night out

for a private duel. At

Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, it

pummels monks up out of

sleep, in Arndorf near Sankt

Veit an der Glan, it

masquerades as a whole box

of stolen reliquaries clutch’d in

the arms of a dying priest.

Its is an act of

coming to whilst arriving at,

it makes of its receipt

a temporary stay, a hemmed-

up moment unhamper’d by rhythmic

palsy’d indifference and its cohort,

the universe, and then it

seizes up and moves along.

—

Piling up weekend mileage, bombing down through the Southern Tier (New York) again. Leaving hardly a thing beyond road listlessness (that state arriving “behind” the tumult of sheer input: weather’d signage and talon-dragging hawks swooping low, the endless green pelt of the hills, the gravel slips of rivers running along the road . . .) Finish’d (in a dribble) Aleksandar Hemon’s book of (loosely) connect’d stories, Love and Obstacles. Wrote “A Year” CCVI in a motel in Horseheads, New York. Ruminated idly on the northerly geographical reaches of the breakfast-offering of (rather gummy) gravy and biscuits, its “spread.” Hemon’s got a narrator in the final story (“The Noble Truths of Suffering”) who asks one “Richard Macalister” (“a Pulitzer Prize winner and acclaimed author”) whom he meets in Sarajevo (“Could he see how beautiful it had been before it became this cesspool of insignificant, drizzly suffering?”): “Did he ever have the feeling that this was all shit—this: America, humankind, writing, everything?” Macalister talks “angerlessly” and the narrator—they’ve met at an evening reception at “His American Excellency” the ambassador’s (“stout, grim, Republican, with a small, puckered-asshole mouth”) house (“famously built high up in the hills by a Bosnian tycoon”) and proceed’d out into the city, the narrator getting drunker and drunker, Macalister not:

Macalister had been in Vietnam, he had experienced nothing ennobling there. He was not Buddhist, he was “Buddhistish.” And the Pulitzer had made him vainglorious—“vainglorious” was the word he used—and now he was ashamed of it all a bit; any serious writer ought to be humiliated and humbled by fame. When he was young, like me, he said, he used to think that all the great writers knew something he didn’t. He thought that if he read their books they would teach him something, make him better; he thought that he would acquire what they had: the wisdom, the truth, the wholeness, the real shit. He was burning to write, he wanted to break through to that fancy knowledge, he was hungry for it. But now he knew that that hunger was vainglorious; now he knew that writers knew nothing, really; most of them were just faking it. He knew nothing. There was nothing to know, nothing on the other side. There was no walker, no path, just walking. This was it, whoever you were, wherever you were, whatever it was, and you had to make peace with that fact.Upshot is that Macalister eventually uses—nigh-verbatim—a later encounter with the narrator and family in a novel. I find myself less took by that than by the overflowing spring of vainglory, that misshapen imp we all know, the one that goes so little identify’d, and less admit’d. Fuck me.

“This?” I asked. “What is ‘this’?”

“This. Everything.”

“Fuck me.”

He talked more and more as I sank into oblivion, slurring the few words of concession and agreement and fascination I could utter. I would not remember most of the things he talked about, but as drunk as I was, it was clear to me that his sudden, sincere verbosity was due to his sense that our encounter—our writerly one-night stand—was a fleeting one.

Aleksandar Hemon

Of Note

Out of Jono Tosch’s terrific chapbook Under Sea (The Chuckwagon, 2009):

Samuel Beckett, Martin BuberA collection of a historical fabulist, full of seemingly involuntary (“natural”) tidbits out of the letters of (mostly) writers, and (mostly) funny (out of “Turgenev”: “‘First thing in the morning,’ he wrote, / ‘Before I even peep at my penis, / I slip out to the boat house and rip a bong. / My novel is deep and wonderful now.’”) So John Crowe Ransom “loved Comet scouring powder”; so Leo Tolstoy admits—“I bought this new LeBaron; I wish I hadn’t.” Recalls some of James Tate’s early deadpan, maybe Russell Edson (though without the constant gratuitous agon). The piece that I remember’d immediately—something of a tonal likeness—Tom Clark’s “Baseball”:

Samuel Beckett disapproved of months.

“Little bastards,” he wrote, “there are too many

of them. What hog made this world?”

Scholars wonder what he meant by that.

Martin Buber offers the following explanation:

“Beckett was a sullen man, and he dressed badly.

You could often see him about town, wearing

as many as three cheap suits simultaneously.

He had incredibly horrible taste in suits.”

In a long letter to himself, Beckett wrote, “You

have become a cloths horse, Samuel.

How many suits does one author need? Fifty?

One hundred? You still disapprove of months.

It is like passing salt to somebody next to you

Who has already finished his soup.”

Scholars are not sure what he meant by that.

But Martin Buber offers this: “Beckett hated

many things; he never celebrated the New Year.”

The Chuckwagon (boost it high in the pantheon of press monickers, I love the name!) is largely the doing of Sean Casey, out of Southampton, Massachusetts. Other chapbooks by Michael Casey, Carson Cistulli, Brad Flis, Loren Goodman, Ben Hersey, Julie Lechevsky, Gerald Locklin, and Isabelle Pelissier, among others.One day when I was studying with Stan Musial, he pointed out that one end of the bat was fatter than the other. “This end is more important than the other,” he said. After twenty years I learned to hold the bat by the handle. Recently, when Willie Mays returned from Europe, he brought me a German bat of modern make. It can hit any kind of ball. Pressure on the shaft at the end near the handle frees the weight so that it can be retracted or extended in any direction. A pitcher came with the bat. The pitcher offers not one but several possibilities. That is, one may choose the kind of pitch one wants. There is no ball.