A Graveyard

Brooklyn’s Archipelago Books prints mostly smallish volumes, in a handsome square format, design work done by David Bullen, who used to do North Point books. A bibliophiliack’s must, what with the classic laid covers, the sharp logo of a tiny “spray” of islands, like a bouquet, or a footprint. The one I examine here, Enrico Pea’s short novelette Moscardino, translated by Ezra Pound, originally done by New Directions (1955), carries a grim Modigliani (The Little Peasant, c. 1918), vacant skyblue-eyes, tiny pinch’d mouth, enormous hat and hands, awkward in the city.

Pound, quoted by Mary de Rachewiltz, out of an October 26, 1941 broadcast, “Books and Music”:

So a few weeks ago Monotti sez: ever read Pea’s Moscardino? So I read it, and for the first time in your colloquitor’s life he wuz tempted to TRANSLATE a novel, and did so. Ten years ago I had seen Enrico Pea passin’ along the sea front and Gino [Saviotti] sez: It’s a novelist. Having seen and known POLLEN IDEN, some hundreds, or probably thousands I was not interested in its being a novelist. But the book must be good or I wouldn’t be more convinced of the fact AFTER having translated it, than I was before. . . .About Enrico Pea, Pound says:

What’s it like? Well, if Tom Hardy had been born a lot later, and lived in the hills up back the Lunigiana, which is down along the coast here, and if Hardy hadn’t writ what ole Fordie used to call that “sort of small town paper journalese.” And if a lot of other things, includin’ temperament, had been different, and so forth . . . that migh have been something like Pea’s writin’—which I repeat is good writing, and was back in 1921 when Moscardino was printed. Moscadino is the name of the kid who is tellin’ about his grandpop, a nickname like Buck.

Like Confucius, knocked ’round and done all sorts of jobs. Writes like a man who could make a good piece of mahogany furniture.Pea, on Pound, whose poetry, “with its sudden interpolations of reminiscences, at time parenthetically incorporated in the rhythm of the song, at times abruptly detached from it,” he’d (c. 1941) barely begun to notice:

I admired his air of civility, and it hardly seemed that his imposing figure, at once primitive and refined, carried the weight of more than fifty years. His bearing was lively: he was dressed with apparent negligence, but actually in clothes of sober good taste. The original pale copper of his somewhat disheveled hair was mingled with the grey due to his years. And the beard, though it covered his chin but sparsely, gave length to his slightly Mephistophelean features.The translation’s got all the stress-fatigue cracks and muddle of a man writing in a language botch’d by long-avoidance. Exactly what makes it “of use.” Look: “The men scratching for mussels in shore with iron pincers stood like the gold hunters in dime novels silently prying off shellfish amid the sieve of sand that the water left alternately dry; sousing in it the motherly water, bitter, pungent with the salt rinsing, then popped it into the wallets slung over their shoulders.” Fleet and rash with gunk’d up pronouns and a kind of Lilliputian Effect (man-shrinkage) occurring at the mention of the “wallets.” I do love what sentences can do.

He would not let me take the brown case that swayed in his left hand. Inside the café, when he opened it on the marble-topped table, the half-moon of a typewriter’s bars made its appearance. The metal clips held a sheet of paper on the roller, and on it were already listed words in the Versilia dialect that occurred in Moscardino.

On these we set to work immediately. As I explained their meaning, Pound typed the English equivalent beside each word.

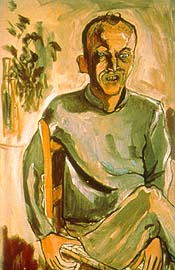

Amedeo Modigliani, The Little Peasant, c. 1918

Through the rain tapping at the yellow slicker the smell of some Cafeteria of the Dead’s leguminous soup, cook’d down to a brick of coagulate, with fatback. Is it the rain itself that alerts the nostrils so? The underscent always that of sea-murk, an oysterish liquor. (A liquoriced oyster.) And, jamming so, I am back to Jard in the Vendée, torching the miniature Carnac of oysters we’d made to stand menhir-upright in the sand, cover’d over with pine needles. A piney residua, boil’d into shell-juices. Arranging oneself against the slight mania rain brings forth, longing for a day of arrangements, aligning huge rocks, moving smallish words into positions of adamance, or rue. Carking a page with the old little words, a word a “stout carl for the nones,” a mean meal of a Sunday, “gray peas steeped in water and fried the next day in butter or fat—” and Etta James shouting about the dead, or the rain.