Sumac

What a sentence is capable of—Javier Marías in Your Face Tomorrow: Dance and Dream, translated by Margaret Jull Costa (New Directions, 2006):

Suddenly, I hear the sound of squeaky, tinny music, like the tone of a cell phone, it took me a while to recognise it—it wasn’t easy—the hackneyed notes of a famous and terribly Spanish paso doble, it was probably that tired old tune ‘Suspiros de España’ which is so often used in my country by novelists and film-makers in order to create a certain tacky, ersatz emotion, (people with left-winger stamped on their foreheads love it as much as cryptofascists do), a ghastly thing, he must have chosen it for his cell phone out of pure racial pedantry, De la Garza I mean, poor De la Garza, and to think only a while ago I had thought ‘I’d like to smash his face in’, I had thought it on the dance floor and afterwards too, with that business of the shoelaces, and perhaps before as well; but it was just a manner of speaking, a figurative use of words, in fact, it’s very rare that anyone actually means, literally, what he or she is saying or even thinking (if the thought has been sufficiently clearly formulated), almost all our phrases are in fact metaphorical, language is only an approximation, an attempt, a detour, even the language used by the most ignorant and illiterate, or perhaps they are the most metaphorical of all, maybe only the technician, and the scientist are safe from it, and even then not always (geologists, for example, are very colorful in their use so language).I like the sprawl, a “hoggishness” with language, splaying out, pushing against its own containedness and precision, a way of getting someplace unbeknownst (hackneyed notes of a paso doble to the language of geologists). “Sufficiently clearly”—a clarity of degrees, somehow reminding me of “I’m not saying it with the proper difficulty”—owning up to language’s way of simplifying. Not a penny—frangipani—for one’s thoughts, the way it is an odor—the stink of thinking—bane like dogbane. (A jazzman’s jasmine metaphor on the run.)

—

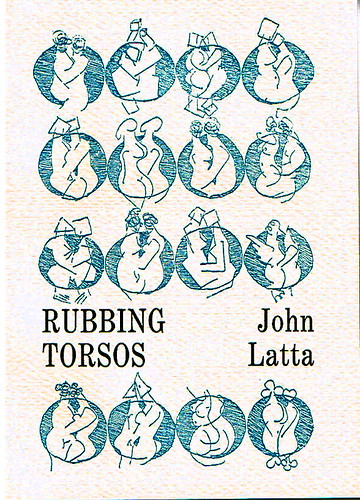

A variation on Bill Knott’s putting all the Knott poems up—I think I’ll ravage my own sorry little archive and—page by page—put up my first book, Rubbing Torsos. The difference: I intend to throw down a running gauntlet of commentary, a ghost (prose) version of Rubbing Torsos, or notes or (hi-di-ho, Cab!) “Krayzie Bone” poem re-versions. Geoffrey Young, in a terrific interview with Thomas Fink, chez Tom Beckett, talks about the poems in Young’s 2005 book, Fickle Sonnets, the poems, according to the book’s Preface, “Serendipity and Method,” being “rewrites of earlier poems originally penned between 1976 and the same year. ‘Whether shorn, expanded, or merely reconfigured’ [the Preface reads], ‘each work’s mind changed, becoming newly svelte, normatively ample, or, like a Costco urn, functionally clunky, depending on the case.’” Young:

Doing Fickle Sonnets confirmed what I already knew: that rewriting is crucial to my process. Not every poem in that book of 112 poems was an old one, though most were. Immersing myself in the process of rehabilitating them, of sending them to weight clinics, or springing them from the anorexia ward, caused me to write 25 new ones, at least. Coming upon some older work in the computer, it’s brutally self-evident what to get rid of, how to streamline, and even what to add, if necessary. That process of editing is a re-thinking; only rarely did the content not shift, mutate into something it wasn’t, before I began tinkering.Excellent. Cost-recovery, weight loss, blunt ouster and brutal replacement, it all sounds like a whoppingly good romp.

Years back in a red-wine, black-teeth spell in Paris, I spent long inebriate evenings thinking about Rubbing Torsos: A Novel. (Recall, there was a sad wayward know-nothing era of experience begat’d art or art (mostly, pitiably, reckonably) traceable—in some truncated way—to experience. I doubt everybody (anybody?) does that kind of thing nowadays. Nowadays it’s slop buckets full of unction and paste pots full of words, and collage is just another way of sniffing one’s glue.) Though “back in the day” (a phrase I find condescending and beastly), well, beastly experience condescended to offer itself up—correct and prim, or all sopping, furry and familiar—for art. And art did diddle it.

The cover: by Pierre Quichy, ancient compagnon of the night-caves of the fifteenth arrondissement. Former member in good standing of the Collectif Zut (circa 1981). Radical misfit in Ithaca turned (briefly) debonair polo-player (yes, on horseback!). Quichy always announced, with cheek and approbation: “Let no line go unlimned, and keep the sketchbook dry as toast. Dry as a fine Chinon.” Of the assembled torsos frottantes, alien copulatives (a kind of poetry), I recall Robert Morgan pointing to the gusto’d pair (second row) just above the winged duckies (whose activities bring a curl to one’s own webbed feet) and claiming: “They’re not rubbing torsos.” And so they mayn’t be. Language is so inspecific and ornery.