Army Life

Deux hommes parurent.

L’un venait de la Bastille, l’autre du Jardin des Plantes.

That’s what the Anglo-French critic Miles Baisers wrote about Jeff Clark and Geoffrey G. O’Brien’s 2A (Quemadura, 2006) in its earlier (French) edition, a sumptuous work of never-tawdry plangency and mollish instability. To evoke Flaubert! how apt! For what is here is various and demanding, ferociously serio-comic, messy and severe toute à la fois.

What there is. Photographs: scratched, spilt with unidentifiable liquids, poorly cropped, Ben-Day dotted into near obfuscatory spleenishness, over-exposed, ill-focus’d, random, murky, unsettlingly aquatic, dated, forlorn, and lovely. There are men in uniforms, boys in ducktails, a girl standing in stovepipe bells in sheer innocent glory on a grand piano, and waves and purses and beach umbrellas and leaves and unidentifiables. A kind of nostalgia seeps out of the photographs, a vaguely “cute” nostalgia one’d like to throttle just to deny the innocence of its call.

What there is. Poems and a longer prose piece titled “Beausoleil.” There are four poems called “Leaves on Sunday” and three poems with the perfectly snarling title of “You and All Your Friends.” One of the “Leaves on Sunday” begins

This close where waste isA dirge undertow, stuttery (like grief?), incredibly moving without a speck of mawkishness, exploratory and tentative: I say all that without knowing precisely what is “going on” here, just extremely willing to fit myself out (or in) (or to) the pace, meticulous and trustworthy, wheresoever it goes. I cannot say it any other way. If the piece reaches a point where it says “The kindness of sure knowledge / edited to make morning plain”—I think of the way language stands in for (I want to say “is a hired dick for”) knowledge, pistol whips it into some semblance of “plain”-ness.

changed somewhat my affections

all the same. Nothing believed

nor motionless this day again

where you remember time

as demonstration, halts to check

who develops, someone taken to

wherever inquiries begin why what

and the stances between, who sentences,

eyes changed from a distance as on

a beach attention is abandoned . . .

The prose piece weaves together the story of “Greg Topper, the once and always king of Orange County rock & roll,” whose act apparently routinely culminated with the torching of both piano and crotch (using Bacardi 151) whilst he bang’d out Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Great Balls of Fire”—and the story / mutterings of Charles Manson: “Are you so white and pure? You put me on Life Magazine and had me convicted before I walked into the courtroom.” (Manson shows up in a later (long) “Leaves on Sunday” piece, too: “Well, Charlie told us to go into the kitchen, get a sponge”—a sense that, re-reading, the reverberations multiply.)

Greg Topper and Charles Manson

“The Rose Shots,” a long (several pages) skinny (no more than one or two words per line) piece (the words array’d around a vertical gap—some puerile novel in my youth call’d it a “vertical smile”): repetition and monosyllabics, a goofy kind of Steinism at work, in play. Reminded me, too, of Ashbery’s great “Litany” (“meant to read as simultaneous but independent monologues”)—although one is syntactically thwarted here reading in either direction, across or down. I cannot replicate it.

A few textual indications point to 2002 for composition date for some of the poems. There is no indication of who wrote what, or even, where the fault-lines lie—swapping lines, or words, or poems. Everywhere though: bravado and surety—“A word is fucking empty until I use it / Why it’s so easy to invent”—wager’d and won.

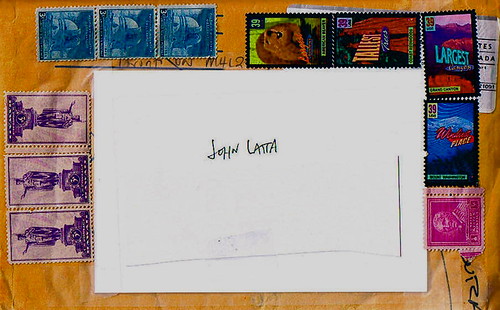

Envelope (Quemadura)

A Rexroth story (out of An Autobiographical Novel):

One sultry afternoon with thunderheads on the horizon but with a clear sky overhead, a fireball materialized in the attic, came down two flights of stairs, passed among a number of people without touching them, went out the front door, collided with a bicycle in the yard, and exploded, leaving nothing but a slight burnt smell in the air. It was sapphire blue, the size of a basketball, and seemed to be spinning at great speed. It floated about four feet above the stairs or ground and preserved that height throughout its course. As the folks said, it moved more like an intelligent being than an electrical phenomenon.