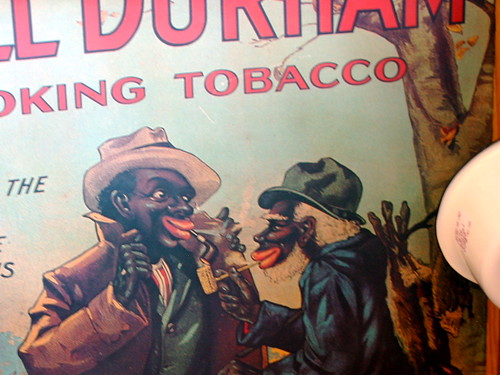

A Tobacco Ad

So the day parcels itself out and adds itself to the diminishing stock, so the sky adjusts its blue, trues it to some imaginary blue it sees mirror’d below it. Walking the cornfields one thinks how geld’d the literary life is. For a long while I claim’d that most of what occur’d to ignite the meagre bonfires of fancy occur’d in the brainpan itself. (The bonfires of the brainpan add themselves to the diminishing stock.) Out in the cornfield roots begin in air. Anchoring rings. Or the cider mill: fifty apples to make a gallon. Mashing a combo of Empires, Ida Reds, Golden Delicious and Mutsu. Not too sweet, with a clear winy after-beat, S. in a “beat” beet outfit: beret and shades and Howl in pocket, beet-colored chinos and workshirt.

Of course, one cannot stray away out of the stench reach of literature long. Stumbling into Dahlberg’s 1952 mock of Faulkner’s Sartoris, (first printed in 1929) wherein he claims “in most of Faulkner’s fiction, the corpse is the hero,” and quotes:

And the next day he was dead, whereupon, as though he had but waited for that to release him of the clumsy cluttering of bones and breath, by losing the frustration of his own flesh he could now stiffen and shape that which sprang from him into the fatal semblance of his dream . . .And, peckishly, rightfully, and puckishly so, Dahlberg lands one on the snoot of a matter rarely ever witness’d in the white rings (annals) of American prose. Of that particular Faulkner, whose “reputation is very stuffed at present” (he’d just received a Nobel), he says: “It was a mournful folly to have published such arrant scribbling the first time, but it is total waste to reprint it when there are poets in America who can’t get printed at all.” Which is precisely how I react to the news that the University of California’s doing Silliman’s Age of Huts (compleat). And “compleat”? Why the goofy eighteenth century orthography tout à coup? I thought that the haven of mad mannerists and covenanters.

Having decried all that, I scoop morning toward me, slathering handfuls of buttery sun, saved up after nights of roaming. I pull down my “Prose Keys to American Poetry” and read:

You come into my life a little yellowThus Ted Berrigan. Because the sun today is a white cross tablet hung up in the errant sky off over “yonder” I’ll repeat a story Kenneth Rexroth relates, how, when he lived in a “basement apartment on Grove Street just off Sheridan Square,” two poets lived upstairs—“Allan Tate and, directly over me, Hart Crane.” Rexroth:

Around the gills and I offer you 41

Pills of indeterminate mixture but you

Will not swallow them you are like

The Sunflower: you are waiting for a

Madman! Now you are like a madam, I

lean over and gaze intently into your

Eyeballs for 32 hours whereupon you swoon

And say, “Perceval, you’re wonderful!”

“Everybody sucks nobody fucks” says John

Stanton in PROSE KEYS TO AMERICAN POETRY

Which I must admit is disconcerting in light of

My premature weaning! Because actually I was in love

With all of those Saturday Serials even if Charley Mackin

did beat me up every week for sixteen weeks

straight! I simply repressed it all!

The week I moved in Crane was busy writing one of his best poems. At that period he was writing everything to what he considered jazz—in this case, Bert Williams’ “The Moon Shines on the Moonshine.” On his phonograph he had one of those old tin contrivances which picked up the needle and sent it back to the beginning of the record with a loud squeak. Hour after hour, day and night, I could hear coming through the ceiling “So still de night, in de old distillery, de moon shine white on de old machinery.” It wasn’t jazz, but it produced “Whitely, while benzene rinsings of the moon dissolve . . .”Where one finds that in Crane, I do not know. I’ll be looking in my PROSE KEYS TO AMERICAN POETRY nightly.