Dylan

New American Writing, No. 24, edited by Maxine Chernoff and Paul Hoover (369 Molino Ave., Mill Valley, CA 94941 / $15 single copy / three issues for $36)

New American Writing is indispensable, unflagging, catholic and open: it caters not to any too narrow coterie. When combined with its Chernoff and Hoover-edited predecessor Oink!—its history now spans more than thirty-five years. Thinking of it, and looking for a couple of early issues (I failed to find), I uncovered a copy of Hoover’s Hairpin Turns, a mimeo’d and side-stapled thing (Oink Books, 1972). For unstinting service alone, Chernoff and Hoover ought to be declared world literary heroes.

A couple of highlights, pointers into the issue. Nathaniel Mackey (interviewed by Sarah Rosenthal):

Coltrane got to the point in some concerts where he would take the horn from his mouth and just start yelling. Rashied Ali, who was the drummer with his last group, talks about an occasion on which that happened. Ali was rather taken aback, and asked Trane about it later. Trane said, “I ran out of horn.” I’ve heard people who do in poetry something that emulates what Coltrane does. They’ll actually scream, do things of that sort. Certainly relative to that I’m very Apollonian. My screaming is going on in a different way. It’s the fraying of meanings; it’s the colliding of sounds that creates certain consternations of meaning that might be the counterpart of the scream, analogous to the scream.Vladimír Holan, translated by Josef Haráček and Lara Glenum:

SufrynkAccompanied by a note: “we chose to suspend the language between Czech and English to give the English-speaking reader a sense that they are reading the poems in the original Czech. We have preserved Czech spelling and inserted Czech diacritics wherever possible. We constantly look for ways to drag the reader toward an experience of the foreign by introducing markedly unfamiliar features of the source text into our translations. By doing so, we hope to interrogate cultural boundaries rather than simply domesticate another culture’s literature into comfortable American idiom. We strive to expose the very act of translation, to make it visible . . .”

In the prekarióz air and with a kolapsedlý gřim

kloud in the background: a mowér is sharpnink hys scýthé,

aš if he wěře úžink a slíče of břed to eřase

centúries-old šmears on a wál in Ekbatan.

Aftěr áll, hošpitáblý nativ frút is not ment fór už,

and hárdly ani sentience kán reašuře už.

Evěn perfekt rezignation styl kňows sufrynk,

and it is sufrynk intimat with the děd, who řely.

An argument I first encountered (I think) in the introduction to Pierre Joris’s translation of Paul Celan’s Breathturn. I like the effect of slowing the orthography demands; it “makes material” the words (as any poetry must); would it begin to cloy, suffer a malign cuteness, become “too much” in a larger selection? I don’t know.

G. C. Waldrep:

What Is a HornpipeMore a kind of Dylanesque American high surreal (that of Greil Marcus’s “old weird America”) than anything so programmatic as the New Sentence. Put down a “he” and a “she” and you got yourself a narrative.

(But when she called to me it was always Mr. Monroe Doctrine, Mr. Monroe Doctrine. I wanted to seize the moment very badly but the best I could do was Brazil. That, or plastic surgery. Or else my ragtime in cold cash. She crossed her arms: Wrong century! Ka-ching. I was devastated. She set a bonfire for my ruffles & jabots. All the small countries attended, even a few that weren’t really countries yet but had set up embassies in hope. It was hard to tell their flags from the flames, at least until I realized that some of their flags were flames. That’s right, I thought, but said nothing aloud. But then she was busy with her welder’s hood and her gemstones. I sauntered over to the concession booth and ordered an Ashoka Pillar with a side of fries. Looking back, that’s what I regret most about those years: the philatelophagy. I was sending messages to all my most elementary particles. Sometimes they would tap back, as if welded into a steel hull. Doomed semaphore! Can a part haunt the whole? I was absurdly coifed. All my friends were working for Parker Brothers. In the end I sold my collection of antique thuribles, no longer having any shelves to store them. She’d say Jump. I’d say How sly.)

———

And a little Written Lives, by Javier Marías, encore and finale.

The names of some of Djuna Barnes’s siblings and ancestors: “Urlan, Niar, Unade, Reon, Hinda, Zadel, Gaybert, Culmer, Kilmeny, Thurn, Zendon, Saxon, Shangar, Wald, Llewellyn.”

Barnes’s fury when Anaïs Nin “took the liberty of using” Djuna for the name of one of her characters.

How the “then unknown” Carson McCullers besieged Barnes’s Patchin Place apartment, “moaning and sobbing at her front door, begging to be let in.” (Barnes herself spent an estimated “more than fifteen thousand days” alone inside that apartment, that is, more than forty years.)

Djuna Barnes

Lord Byron’s lisp.

—

Emily Brontë’s love of target shooting, with a pistol.

———

A dreamed sentence: “A book is both a ticket out of here, and a culprit-seizure of the inescapable.” (After shenanigans of searching for a lost boy, and a lost Tupperware container, and witnessing the expulsion of a couple of Pakistani, or Sri Lankan, women suspected of “gang activity”—via codewords in the CDs they played—out of a resort. An expulsion that left us comrades trudging along a dust-stirred road.)

—

Reading Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale.

—

Rereading the Biographia Literaria.

———

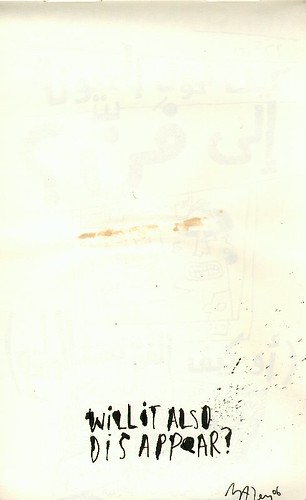

And Mazen Kerbaj drawing with coffee and ink in Beirut: