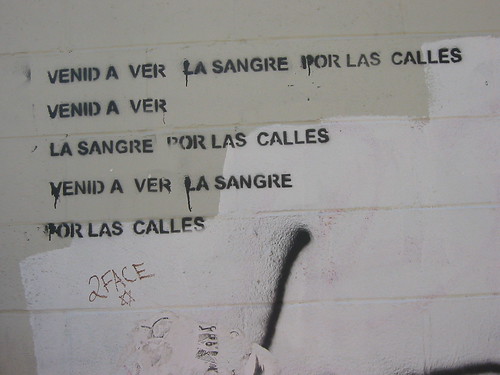

La Sangre

Finished, reluctantly, the Weiss book, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Near the end he examines two paintings—unfamiliar ones to we who come up trained to consider art’s “formal” questions foremost. One painting is Adolf Menzel’s “picture, eight feet wide, of an iron-rolling mill.”

Adolf Menzel, The Rolling-Mill, 1875

Weiss, on worker culture and the representation of workers (looking at the historical moment when workers begin to be painted, or sculpted, or “put into” writings, “released from their insignificance”:

. . . the depicted worker was never seen by himself, he was always seen only by the artist, by members of a different sphere of life. We . . . expressed ourselves solely in our labor, we very seldom got to view what was captured of us in art. We dealt with our tools, our art was cultivating the soil, grafting the fruits, building the houses, these things called for songs, fables, fairy tales, handed down orally, we never made a fuss about the things we signed with our names . . . Our culture is lugging, pulling, and lifting, tying together and fastening. This culture comes toward me . . . whenever I see someone piling the chopped wood, sharpening the scythe, mending the net, joining the beams in to the roof frame, polishing the pistons of the machine.That is, rather than accepting the view that “only in an artwork that labor had cultural meaning, it was only there that labor had become art, while the workers themselves remained without rank,” the need to recognize art outside the confines of “the official,” “the artistic.” Weiss: “because of the growth of a conscious working class the recognized official art had provided a place for workers, a place for them to make their presence felt . . . the establishment had, at the same time, skillfully reneged on its generosity.” A close reading of Menzel’s painting allows Weiss to conclude in part: “All they [the workers] are doing is thoroughly confirming the rules of the division of labor. They appear to be acting on their own, but the exist only in their bond with the tool and the machines, which are the property of others.”

Robert Koehler, The Strike, 1886

On a painting titled “The Strike” (1886), by American artist Robert Koehler, “taken from an old edition of the magazine Harper’s Weekly” and “shown at the Paris World’s Fair of eighteen ninety-nine”:

. . . it was a straightforward illustration, excluding any question about technique or composition and focusing our attention solely on the content. To the left, the plant owner had stepped out of his mansion with its portico. He stood at the top of the steps, behind the ornamented cast-iron railing, elegantly dressed, in cuffs, a stand-up collar, and a top hat, pale, white-haired, and grim, raising the fingers of his right hand as if holding a cigar, but the hand was empty, the gesture expressed surprise, a powerless staving-off. Though he towered above the people in front of him, and though his attitude was still marked by the self-assurance of a class that could not imagine giving up its privileges, it was nevertheless obvious that he was confronted with a growing power that could effortlessly teach him how ephemeral he was . . . all his courage boiled down to one thing: it was inconceivable to him that the workers could climb up to him and tear him down . . . The group of workers gathering in the empty area in front of the house seemed to contain all the possible ways in which the conflict could develop. Clenching one hand in a fist, stretching the other toward the factory, whose chimneys, unlike the industrial smokestacks on the hazy skyline, were not smoking, the spokesman faced the boss directly at the steps, while the others, waiting in various degrees of menace, observed the dispute or debated intensely among themselves. A woman was trying to calm one of the workers, whose gestures indicated that he was out of patience, that something had to happen right away, and a man in the right foreground, wearing a cap of folded paper was bending over to pick up a stone from the dusty soil. They had come out of their brownish-black, castle-like factory, they were unarmed, they had been ground down long enough, they had angrily run down the hill to the stairway, the last members of the work force were hurrying out of the smoked-up building, even the coachman had left his team in the clayey hollow. The grab for the stone, a gesture repeated in the background, was the signal that violence was taken to be the sole possibility. The factory owner stood cold and rigid, as an individual, and the workers possessed devastating superiority. Nevertheless, the gentleman remained unapproachable. The stone would not be hurled. Whatever would result from the given situation, it halted at the threshold of the stairs. The movements of the workers standing farther off were full of indignation, resolution, near the brick mansion they yielded, became more hesitant, preferring to wait and see, yet not without courage. The house would not be stormed because the workers knew about the power that protected the arrogance of the morbid gentleman. Behind the house stood, invisible, the heavily armed national guardsmen.Weiss continues, pointing to Koehler’s understanding of the workers, who, “self-assured and not spellbound by the production of wares,” how any “isolated attack would have made no sense, they would have been mown down on the spot. The furious waiting, the shaken fists were harbingers of measures that had to be taken with the framework of an organization.”

On Koehler and the painting’s evident insertion into history (art as wedge):

Eighteen sixty-eight, that was the year when the mass strikes began in the United States, when workers, demonstrated for the eight-hour day, and when, on the first of May, a demonstration of workers was bloodily crushed by the Chicago police. The picture painted by Koehler, born in Hamburg in eighteen fifty, died in poverty in Minneapolis in nineteen seventeen, retained its contemporary quality as undisguised testimony to the antagonism between the classes. The labor union had been founded, but its leaders had been corrupted, had been bought by the enemy, the proletariat was still faced with the urgent task of changing its situation.—

How close comes Ozarker fictioneer Daniel Woodrell’s sketch of the “faculty poet” (out of Give Us a Kiss: A Country Noir (1996):

. . . an imperious li’l tub in his late forties who jiggled when he walked and had a huge messy beard that was supposed to indicate he was too far gone into meaningful thought to bother with bourgeois grooming. He specialized in tiny odes about playing Wiffle ball with his daddy as the Pittsburgh sky grew gloomy, epiphanies he’d had while dieting, and baseball as a metaphor for something I forget. He was unaccountably popular and heavily clapped over in the quarterlies.And here we thought only Heap Big Chief post-avanters deigned to mock the popular duds.

(The main character Doyle Redmond arrives West Table, Arkansas in a stolen “stagnant pond-green” Volvo with, besides “traveling clothes, “one box of books,” “books I never left behind and made any crap hole I landed in home to me”:

There were a couple of Elizabeth Bowen novels, a quartet by Edward Lewis Wallant, one volume of Pierce Egan’s Boxiana, The Williamsburg Trilogy by Daniel Fuchs, Carson McCuller’s oeuvre, a stack of Twain, a batch of Erskine Caldwell’s thin li’l wonders, some Liam O’Flaherty and John McGahern and Grace Paley and Faulkner, all of Chandler, and a copy of Jim Harrison’s A Good Day to Die. Also, a jumbo volume of Robinson Jeffers poetry, and various guideworks to flora and fauna. Dictionary and thesaurus, of course, and my boot-camp yearbook from Platoon 3039, which would have been my junior year in high school.As good a starting place for a writer as any, unless one’s a diehard freak for the ordinary bifurcation of “lineage” and conceives of American poetry (at least) as wholly swiveling around—radiating into and back out of—one great grey granite slab of authority known as “the Allen anthology.” And that’s the second incidence of somebody pointing to the Daniel Fuchs trilogy lately—Jonathan Lethem named it on some “neglected” list or other.)