Some Shoes

Yesterday with its “nobody ever was that man” leap into the historical light, a dazzling way to forego ending. What I mean is, I intended something else—intended a “rangier” look into Berkson’s Sudden Address, got hung up by the O’Hara stories in a kind of willing bliss—and puddled (into) myself. A sort of “I wonder if I’ve really scrutinized this experience like / you’re supposed to have if you can type” thing (I love that grammatically correct insert of “have” there, raising irony’s bar). So, seeing’s how I cannot breach the psychoanalytically-soggy reports of Steve Benson’s early manhood pangs (replete with thirty year old journal “entries”) that open the latest volume of The Grand Piano, I elect to continue prowling the Berkson book.

If more proof’s needed of Berkson’s sense of “method”—in the middle of prefatory remarks to a slide lecture (present’d at the Poetry Project (1984) and New Langton Arts (1985)) titled “Idealism and Conceit (Dante’s Later Thought)”—he remarks that the talk “is meant as an entrance to the topic with banged-together quotations; a roughing-out, a spillway, a pounce, a show and tell with pictures as points of refraction as if we were speaking at your house / my house with concomitant ‘wild surmise.’” The way all discourse ought to be. After all, it’s only us blowhards pushing our gassy inconsequentialities into the whistle holes of a runaway train, just to see if they’ll sound loud enough and with enough “leeway” that that flapper (who is ourselves) tied to the tracks’ll be able to unknot inscrutable knots . . . (she won’t, we won’t, death’ll “greet” us all). Just horses running the field, nicking the turf nick’d by horses ruining the field. (A spillway is not a metaphor race.)

Metaphors. Berkson quotes Williams’s prologue to Kora in Hell. Williams may or may not be talking about marriage to Flossie. He’s certainly talking about one’s early spurts and drenches of “poetry”:

I have discovered that the thrill of first love passes! It even becomes the backbone of a sordid sort of religion if not assisted in passing.(And one could “tick off” any number of poets of the current “order” for whom “first love” never did get the comeuppance it required. Legion, indefatigable, tiresome repeaters they be.) Against that impulse (need) to rid oneself of one’s initial adorings, those “oddball” burgeonings forth that led one to the act of “making art,” Berkson puts “returning to that original rock”:

Artistic vitality is partly a sporadic re-acquaintance, a reconnoitering of one’s original feelings about art, turning them over and seeing what’s inside and under them.(And, though Berkson’s thrust is toward the individual, one’s allow’d—ontogeny reciprocating phylogeny—to apply the continual re-circulating back to source to ever larger entities: literary history spiraling in lieu of flat-lining.)

Truth is, I return, I am no better off—Berkson’s bounding through quotables like a pup. He says: “My mind feels like St. Jerome’s little terrier; not as well-groomed, I suspect, but at least sparking upright, a kite in the fog” and proceeds to will that the talk “tumbles somewhere between connoisseurship and oratory.” Elsewhere, he notes, approvingly: “Guston’s ‘I want to end with something that will baffle me for some time.’ Where baffle is a transforming device that deflects, furthers circulation, heats shot with gleams, “the mirror living which art is.” The apparent motto is: ‘Quit quoting.’” All velocity and muster, and, yes, “sparking.” Maybe it’d be of use to suggest the range of material and leave it for readers to rush it together. Poetry and painting intertwinings, Guston, Alex Katz, Franz Kline; Philip Guston, memoirs of (with comments on particular works, and quoting, amongst others, Robert Smithson and Clark Coolidge); the “Idealism and Conceit” piece, with a handy summary of “sources of quotation and / or allusion”:

Osip Mandelstam, Joseph Anthony Masseo, Ted Berrigan, Clark Coolidge, William Carlos Williams, Dante Alighieri, John Thorpe, Jack Spicer, Erwin Panofsky, Wallace Stevens, Adrian Stokes, Samuel Edgerton, Francis Ponge, Philip Hendy, Philip Guston, Juan Gris, Henri Focillon, Alex Katz, Willem de Kooning, Morton Feldman, Albert Blankert, John Montias, Roberto Longhi, Paul Cézanne, Samuel H. Monk, Oxford Dictionary of the English Language, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Alfred North Whitehead, Justin Kaplan, Walt Whitman, John Ashbery, Tom Clark, Edwin Denby, Carter Ratcliff.“History and Truth” with Stein, Creeley, Diderot, Auden, David Antin, and “Frank O’Hara’s most cogent political statement, “the only truth is face to face”; a piece about Whitman, with Baudelaire, Courbet, Williams, Reznikoff, Bernadette Mayer; the O’Hara piece; and a final piece titled “‘The Uneven Phenomenon’—What Did You Expect?” that is—partially—a memoir of Kenneth Koch.

—

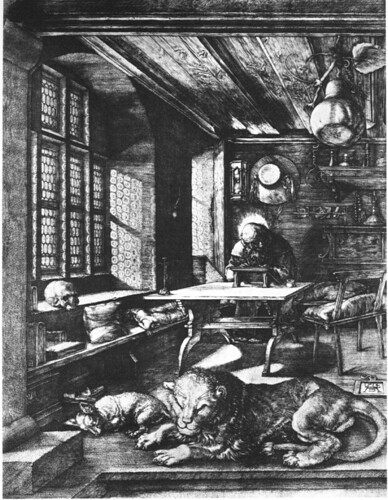

Morning. Spent a little while looking for “St. Jerome’s little terrier” amongst the scads of St. Jeromes, with tepid result. Us bang’d up necessary contemplatives need a dog named Sparky. Dürer’s beast certainly looks perky enough, though not what I expect’d. I want’d to find a Dutch terrier, noted out the slant window of Jerome’s “cell,” implausibly leaping for a miniature halo’d insect, a lightning bug.

—

Long weekend upcoming. À mardi.

Jan van Eyck’s St. Jerome

Albrecht Dürer’s St. Jerome

Antonello da Messina’s St. Jerome

Somewhat later. Bill Berkson writes to identify the long-sought terrier, the rather demure beast of Vittore Carpaccio. One sees each—St. Jerome and dog—stunned by seeing. (What each sees is another matter.) Note, too, the various volumes upend’d and splay’d here and there, and the flung-down fold’d letter. The dog’s work or St. Jerome’s? Ah, the fits of the contemplative . . .