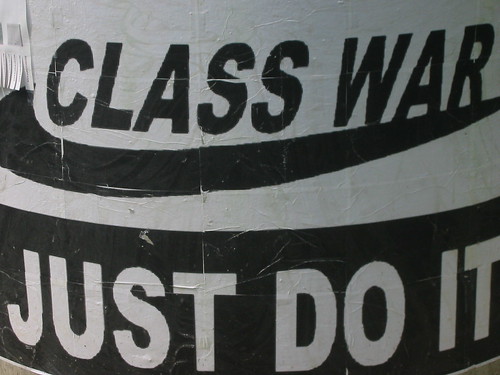

Class War

Javier Marías in Your Face Tomorrow: Fever and Spear, translated by Margaret Jull Costa (New Directions, 2005):

Life is not recountable, and it seems extraordinary that men have spent all the centuries we know anything about devoted to doing just that, determined to tell what cannot be told, be it in the form of myth, epic poem, chronicle, annals, minutes, legend or chanson de geste, ballad or folk-song, gospel, hagiography, history, biography, novel or funeral oration, film, confession, memoir, article, it makes no difference. It is a doomed enterprise, condemned to failure, and one that perhaps does us more harm than good. Sometimes I think it would be best to abandon the custom altogether and simply allow things to happen. And then just leave them be.Ironic that, shortly after noting that, I should come across—in the course of investigating the story of the disappearance of Andrés Nin, leader of the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, an anti-Stalinist revolutionary groupuscule in Civil War era Spain), apparently tortured and killed by Stalin’s agents—a death that’s part of Marías’s novel and, too, part of Peter Weiss’s Aesthetics of Resistance—these remarks by George Orwell:

I know it is the fashion to say that most of recorded history is lies anyway. I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased, but what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written. In the past people deliberately lied, or they unconsciously coloured what they wrote, or they struggled after the truth, well knowing that they must make many mistakes; but it each case they believed that ‘the facts’ existed and were more or less discoverable. And in practice there was always a considerable body of fact which would have been agreed to by almost everyone.The kind of thing that’s apt to heave a sledgehammer after the fly in the postmodern ointment. Apparently, Nin, a figure, too, in Catalonia’s literary and linguistic revival, translated Dostoevsky and Tolstoy—versions read still.

Andrés Nin

Tepid times. Dog of a cynic’s brow. I see there’s an excursus on the issue of the poetry “book” as opposed to the “collection” (of poems). Against the vagary of disjoint, the omnium of posies gathered willy-nilly, the proud prow of a more majestic battleship moves out (into the careerist-infested waters). Truth is, the “book”—once a suitable shtick is summoned, O ye muses!—is a vastly less demanding “enterprise.” One no longer confronts a succession of blank pages, and the demands of the immediate “moment,” one is “filling in” the gaps in a trajectory, episodic, plotted, or pre-determined (Alabama to Wyoming, I to CLIV, Hydrogen to Lawrencium, A to Z).