Stop

Time’s adipose inconstancy, its longueur and accelerations, the weekend left its bruise nowhere on the week, meaning to say, no (little) writings accrued. Hence a vagary of morcels, sliced off the literary cheese. First: Genet on Rimbaud:

“O let my keel burst! Let me go to the sea!”And, the turned obdurate and contemptuous misanthrope Melville, in Pierre or, The Ambiguities:

What’s surprising is that “O let my keel burst!”—the boat itself says that, the Drunken Boat, and in slang “keel” [la quille] means “leg.” When he was seventeen, Rimbaud said: “O let my keel burst!” That is “O let my leg . . .” And at thirty-seven he had his leg cut off, by the sea, at Marseille. That’s all I wanted to say.

There is, it seems, though I can’t prove this, with every man, every man, whether a poet or not—“poet” doesn’t mean much—but with every man there is, at a given moment, something like a prophetic gift with regard to himself, that he himself does not see. I’m convinced that Rimbaud meant to say, and did say, that his leg would be cut off. I’m convinced that he wanted his silence. I’m convinced—to stay within the realm of the poets—that Racine wanted his silence; I’m convinced that Shakespeare really wanted anonymity, in the end, and Homer too.

He could not bring himself to confront any face or house; a ploughed field, any sign of tillage, the rotted stump of a long-felled pine, the slightest passing trace of man was uncongenial and repelling to him. Likewise in his own mind all remembrances and imaginings that had to do with the common and general humanity had become, for the time, in the most singular manner distasteful to him. Still, while thus loathing all that was common in the two different worlds—that without, and that within—nevertheless, even in the most withdrawn and subtlest region of his own essential spirit, Pierre could not now find one single agreeable twig of thought whereon to perch his weary soul.And, Javier Marías, in All Souls:

Everything that happens to us, everything that we say or hear, everything we see with our own eyes or we articulate with our tongue, everything that enters through our ears, everything we are witness to (and for which we are therefore partly responsible) must find a recipient outside ourselves and we choose that recipient according to what happens or what we are told or even according to what we ourselves say. Each thing must be told to someone—though not necessarily always to the same person—and each thing will undergo a selection process, the way some one out shopping one afternoon might scrutinise, set aside and assess presents for the season to come. Everything must be told at least once although . . . it must be told when the time is right or, which comes to the same thing, at the right moment, and sometimes, if you fail to recognise that right moment or deliberately let it pass, there will never again be another. That moment presents itself sometimes (usually) in an immediate unequivocal and urgent manner, but equally often, as is the case with the greatest secrets, it presents itself only dimly and only after decades have passed.Meaning, one supposes, that by not writing (every day and minute of not writing), one is not “putting off” a thing—one is losing (irrevocably, no calling it back) a thing. Arrêtez ces conneries . . .

—

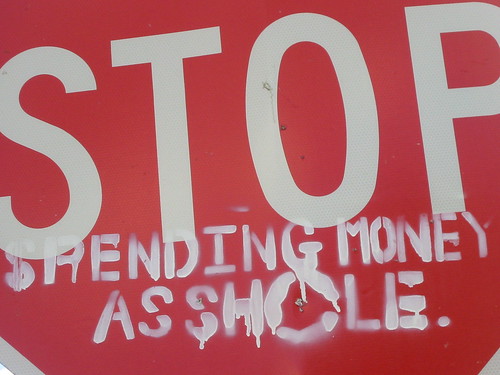

Scott Keeney’s resumed “Nobody in the Rain” with, amongst other things, some terrific Stop graphics. Kin to my tiny collection of photographs of stencil’d Stop signs.