Two Hollyhocks

1

I think I’ve begun about fourteen reviews of Kent Johnson’s new and terrific quasi-select’d

Homage to the Last Avant-Garde (Shearsman, 2008) by now, all stow’d up in my tiny brainbox. It’s a big mystery why I can’t put any of it down on paper. Kent Johnson keeps saying, “I’d love to know what you think of the book,” and I say, “Patience, Master, patience” as if I were cloistered in New England with a slightly puffy physiognomy behind which I build little spring-traps of syntactical ingenuity about trapping God, or someone rather “like Him.”

2

Is Kent Johnson a nervous Nellie, or what? I think he positively

thrives on yatter and scorch, that version of the lyrical big itch that accounts for Art and Trouble (two manifestations of one compulsion) amongst all us humankind. He’s always looking to “mix it up a little,” flinging down the fat puff’d up old-style boxing gloves of ego for a little delight in exchange and engagement. Man least likely to consider (or

care) about the possibility of looking a little foolish. Besides, he

likes people, in all the muddle and mayhem and mopery. And then there’s Kent Johnson backing off a little, peevish and bewilder’d: “I must be the biggest pariah in Poetryland by now.” “Nobody’ll even

talk to me.” Endearing crazy vulnerability

and that obscenely huge grease-slick of high ambition. And all of it highly nuanced and terrifically “up front.”

3

One thing I love here in the

Homage: how some of the select’d pieces—old “rocks” out of the now-classic pamphlets

The Miseries of Poetry and

Lyric Poetry After Auschwitz—get new settings, to shine slightly abashedly and askance in a book model’d pertly after Jack Spicer’s

Book of Magazine Verse. Here’s the old Skanky Possum chapbook of Greek poems “drawn from glorious antiquity,” aimiably English’d with the assistance of Alexandra Papaditsas, “victim of the rare syndrome

Cornuexcretis phalloides, wherethrough a large keratinous horn grows from the head,” become “Twenty Traductions and Some Mystery Prose for

“C”: A Journal of Poetry. (One only misses the forty some “blurbs” for the work Kent Johnson coerced out of an equal number of comrades through, undoubtedly, promissory puling and sexual shenanigan.) And here’s the brute

avant-castigatory mode of the Effing document with the Adorno title become “Seven Submissions to the War for

The World. One is forced to consider (imagine) the alignment of lines like Kent Johnson’s “Listen, Tawfiq, you

tafila, / OK, so you’re a sorry-assed academic with a Ba’ath mustache, / but put your brains back into your head” next to early

World-fodder like Ted Berrigan’s “The true test of man is a bunt” or Joel Sloman’s piece listing the measurement of each part of ’s body, and wonder at how irremediably the world’s changed. It’s an audacious move, part of Kent Johnson’s continuing project of swiveling the telescope back around to examine its own makers.

4

Continual restlessness, constant reprise, incessant renegotiation of a poem’s

place vis-à-vis the world, its audience, its

mise en scène: the grand upshot of Kent Johnson’s energetic

tampering with the status quo is a kind of radical confoundedness. “Uh, where the hell

am I?” Kent Johnson’s admiration for (some ’d claim

emulation of) the heteronym-donning Fernando “Person” Pessoa is well-known: during one period in the late ’nineties I suspect’d a whole slew of rather ordinary people of being somehow “projections” of Kent Johnson—Kazim Ali, Patrick McManus, Paul Murphy, Ron Silliman, Jacques Debrot, Jeffrey Jullich, Jordan Davis, Geoffrey Gatza, Millie Niss, Eliza McGrand, Mikhail Epstein, and innumerable fleeting “others.” (Anybody recall one “Ammonides” writing in to the Poetics List?) Setting aside, though, the rather tiresome subject of “the subject,” (multiplicity of, author-function no longer singularly assignable to, &c.), what one encounters in the shifting panoply of works of Kent Johnson is something like what Harold Rosenberg call’d an “aesthetics of impermanence,” wherein circulation and intervention become of primary concern. Not the static masterpiece unchanging, but the pertinent (potent) gesture

for the current moment. As such, what one sees come forth in Kent Johnson’s

Homage is adamant certain re-contextualization: how it needs read

now. The effect is often vertiginous: every piece seems familiar, every piece seems “off,” and sublimely new.

5

One of the “Five Sentimental Poems for

Angel Hair” is a piece about fishing, and fathers and sons, and truths and falsehoods, and making do,

and it’s about John Ashbery’s poem “Into the Dusk-Charged Air” and Frank O’Hara’s “Why I Am Not a Painter,” countless things. It’s titled “Sentimental Piscatorial”:

The fishing was good this morning, though

we never made it to the Mississippi. The Apple

is a lovely tributary; once I almost drowned 1

in its green, but that was a long time ago,

and I didn’t, because I guess life still

needed something there. Well,

for instance, as I said to my son Brooks,

who is starting to be a poet, many times

(as I’ve said many times to him, that is), if 2

you are going to put your life into

poetry, make sure you stay low, walk slow,

and lay the fly right along the velocity

changes. The sun was just starting to burn-

off the fog, and a doe walked across the riffle

right upstream and didn’t startle. A hereon stood

in the next pool, shimmering, “like

some kind of religious lawn ornament,

when you think about it,” my son 3

said. And so I watched my son fish,

covered in an actual gold, like his

drug-inspired poem of the alcoholic man

with the burning city in his heart. I 4

watched him fish, trying so to impress me,

his back to the sun. 5

1 The first stanza is, perhaps over-obviously, an allusion to John Ashbery’s “Into the Dusk-Charged Air.”

2 The second and third stanzas are prosodic glosses on Frank O’Hara’s “Why I Am Not a Painter.” Interestingly, the following email response was received from Hilton Kramer, editor of The New Criterion, to whom this poem (sans footnotes) was originally submitted: “Dear Mr. Johnson, I like the poem quite a lot; it has an easy and laconic sound breaking elegantly across an unusual and complex meter (the ionic as base foot is idiosyncratic, to say the least, and quite impressive). Still, I am afraid I have to pass this time around—Guy Davenport, who has the last word with all poems submitted to NC, felt that the poaching, as he put it, from O’Hara in the second and third stanzas was too cute and obvious. But I will tell you that Mr. Davenport found the poem’s ending “strangely moving,” and I can tell you, too, that he doesn’t often offer up such words as “moving” in his reports to me. Please do send us more of your poems. —HK.”

3 When Brooks was a child, I would read him poems at bedtime. Wallace Stevens (the Stevens of Harmonium) and Kenneth Koch were his favorites. I now realize that Brooks would never have said what he did about the heron appearing as a lawn ornament had it not been for Koch’s line in that love poem about the parts of speech, where the garbage can lid is smashed into a likeness of the face of King George the Third.

4 This is an allusion to St. Augustine’s City of God, which is the theme, if you will, of my son’s painting. In the upper corner of the canvas, in tiny, calligraphic lettering, my son has written the following passage from Augustine’s Soliloquia, which he copies from Doubled Flowering: From the Notebooks of Araki Yasusada, the heteronymous masterpiece of “Tosa Motokiyu,” of whose manuscripts, it is by now widely known, I am one of the caretakers:For how could the actor I mentioned be a true tragic actor if he were not willing to be a false Hector, a false Andromache, a false Hercules? Or how could a picture of a horse be a true picture unless it were a false horse? Or an image of a man in a mirror be a true image unless it were a false man? So if the fact that they are false in one respect helps certain things to be true in another respect, why do we fear falseness so much and seek truth as such a great good? Will we not admit that these things make up truth itself, that truth is so to speak put together from them?

5 This is an allusion to an image in a poem by Whitman, where the sun behind a man standing in the water forms a golden aura around him. But I cannot now recall the exact poem.

All that makes for a reading experience that simply

teems with possibility and complexity. There is, undeniably, something “moving” at the center of it—though the evident knowledge of the “false Andromache” that produces that emotion be unstinting, ineffable. There is, too, the complicated play between private and public Kent Johnsons: whole vasty degrees of difference ranging from denial-stealth (“almost drowned / in its green, but that was a long time ago, and I didn’t”) all the way up to something like braggart-exhibitionism (“the heteronymous masterpiece of “Tosa Motokiyu,” of whose manuscripts, it is by now widely known, I am one of the caretakers”). And interlard’d with

that complexity, is one of degrees of truth and falsity (“how could a picture of a horse be a true picture unless it were a false horse?”) And that (complexity)’s most acute pressure point is—both here, and generally—for Kent Johnson the place of the writer’s

habitus, the charm’d and charmless, petty and fetter’d, large and

withholding multitudes milieu of the writerly “scene.”

6

What Kent Johnson does—unlike anybody else—is interrogate (badger) that place, that “situation,” its ways and functions, how its writers behave and misbehave, lie to others and themselves, trade favors and insults, pose, vindicate, prance, vilify. So that: a note (apparently) written by

The New Criterion’s Hilton Kramer, mark’d arch-nemesis on

some presumptive rulers’ cosmological maps becomes an integral part of Kent Johnson’s “sentimental” poem. And yet: that radical confoundedness (“where the hell?”) raises up like a myrmidon: that “laconic sound breaking elegantly across an unusual and complex meter (the ionic as base foot is idiosyncratic. . .)”: uh, who’s zooming whom? One’s enter’d a world where the usual landmarks may be topsy-turvy, the nemesis may be correct, “Mr. Davenport”’s report additional proof, and the fact that “the sun behind a man standing in the water forms a golden aura around him” noteworthy only for the its being the case for

anyman, or Everyman.

7

Or: here’s what William Gaddis (in

The Recognitions) had to say about the poems of Kent Johnson:

Like a story I heard once, a friend of mine told me, somebody I used to know, a story about a forged painting. It was a forged Titian that somebody had painted over another old painting, when they scraped the forged Titian away they found some worthless old painting underneath it, the forger had used it because it was an old canvas. But then there was something under that worthless painting, and they scraped it off and underneath that they found a Titian, a real Titian that had been there all the time. It was as though when the forger was working, and he didn’t know the original was underneath, I mean he didn’t know he knew it, but it knew, I mean something knew. I mean, do you see what I mean?

“Something knew.” One of the reasons why Jack Spicer is so central to Kent Johnson’s poetics—that ability to allow the “radical confoundedness” (“This is getting good, isn’t it?”) to out (and it may do so over the erring wanton interventions of several occasions—like sending a poem to

The New Criterion). The Jack Spicer, who says (in the 1965 Vancouver lecture “Dictation and ‘A Textbook of Poetry’”):

. . . there are plenty of times when you're so busy writing it and you have to wait for two hours because the thing is coming through in a way that seems to you wrong. It may be that you hate the thing that’s coming through so much, and you’re resisting it as a medium. Or it may be that the thing which is invading you is saying, “yeah, well that’s very nice but that hasn’t anything to do with what this is all about.” And you have to figure that out, and sometimes it takes a number of cigarettes, and occasionally a number of drinks, to figure out which is which . . .

Or a number of “presentations.”

8

Is Guy Davenport right? About the “cute and obvious”? Yes, of course. Guy Davenport’s

always right. And yet: it is by means of such ploy (faux-innocence gamboling) that the stage is set. (See Kent Johnson’s opening query to “The Best American Poetry”: “Am I the only idiot here, on this hill, surrounded, as I am, by rutting rams and heated ewes?” And moments later one sees James Tate and Dean Young approach, with one loud “Baa-a” and another loud “Baa-a” in return. About as “cute and obvious” as an AWP Conference or an evening reading at the Poetry Project. The honest-to-God fun comes—as it generally

does in a Kent Johnson poem—when, confront’d with a burning house, the poets on the hill “squint and espy the ant-like people, running around or passing water buckets in a line. And there goes the little red fire truck, speeding towards its fire, pulled by Gertrude, the ancient Clydesdale.” The house, of course, belonging to one Hejinian.)

9

If I find a hero in

Homage to the Last Avant-Garde (a funny thing to look for in a book of poetry), it’s Arkadii Dragomoshchenko. In a poem in the form of a letter to David Shapiro, Kent Johnson writes “Yes, it’s true, the Language poets air-brushed me out of Leningrad” (see the collaborative book,

Leningrad by Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, and Barrett Watten about the August 1989 “international conference for avant-garde writers”). And, while offerings of official “formal toasts to the ‘American Poetic Friends of the Soviet Union’” continue “in a vast hall in a vast, ornate czarist building made all of marble, crimson-draped windows towering to the ceiling, looking out onto the Neva, swarms of cherubs fat and hot for Aphrodite above, a U. S. avantist facing me across the great mahogany table in a kind of late pinkish glow, dapper Aeneas in a polo shirt,” it is reported how hero Arkadii Dragomoshchenko “leaned over to me and with booze on his breath said in heaviest accent, ‘Is this a great quantity of such repulsive fucking dog shit or what?’” (Though not—and here’s Kent Johnson’s genius—to skip out on the indictment, Kent Johnson offers a reply: “‘You think so?’ I burbled, my mouth full of bread and sturgeon eggs. ‘Why, it’s the first time in my life that I feel like a real Poet . . . I think this is fantastic!”)

—

THE EVERYDAY64

The orchestra conductor tells the drummers that the beat needn’t be

loud so long as it is

inexorable. “I love that word,

in-ex-or-a-ble,” he says, weighing it, tongue-ing its syllables unmitigatedly.

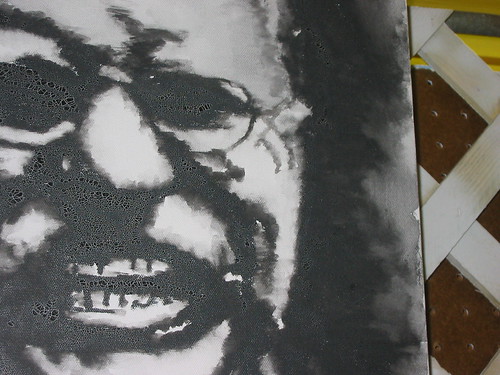

Kent Johnson in La Paz, Bolivia, with Flowers, 2004

(Photograph by Forrest Gander)